The number one question we get at the Low Technology Institute is, “What — exactly — do you do? Your research and offerings are kind of all over the place.” And this is true. Our research spans beekeeping, solar hot water and heating, potato husbandry, flax growing and processing, self-provisioning, composting, and much more. Our classes have ranged from harvesting and processing wheat without machines and venison butchery to shibori (Japanese indigo dying) and timber framing.

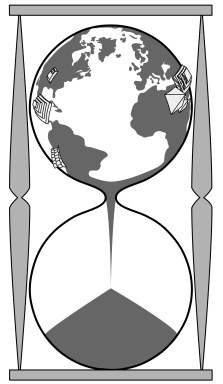

Why is the scope of our research and classes so broad? Because life is big and multifaceted. Our goal is to develop strategies to house, clothe, and feed ourselves in a future without fossil fuels. In other words, we’re trying to figure out how we’re going to live comfortably and sustainably in a quarter century. This future requires a broad set of skills within each community and we want to help people develop that experience. It is ambitious and more than a single person — or organization, for that matter — can take on alone.

Cassandra: Blessed with Foresight, Cursed with Rejection

Although it is hubris to compare our mission to the classic figure of Cassandra, the parallels of our organization and the Trojan woman are obvious. Once upon a time, in Classical Greece, the god Apollo wished to win the favor of fair Cassandra, sister of Hector, famous for his role in the Trojan War. He gave her the gift of foresight and prophesy, but she then either reneged on past promises or failed to be won over (opinions vary). Unable to revoke the gift, Apollo added to his initial endowment that her foretellings would be disbelieved.

We’ve said many times, in many places that the past was, and the future will be, free of fossil fuels as we currently know them. We also say often that we have two choices: voluntary abdication or involuntary collapse. You can either have a smooth dive or a belly flop, but gravity is immutable. If I told you the economy and world transportation system was going to collapse in twenty-five years, would you start to arrange to live in a self-sustaining way now? Okay, then I am telling you that without major changes to our infrastructure (i.e., complete electrification and reduction of energy use in the next decade), our economy and transit system will collapse in twenty-five years.

Cassandra cried, and curs’d th’ unhappy hour

from Book II of Virgil’s AEneid, translated by John Dryden

Foretold our fate, but, by the god’s decree,

All heard, and none believ’d the prophecy.

If you google, “How many years of oil left?” you get 47 years (current consumption divided by known reserves). But that assumes we can extract all that crude, and we’ve pumped the easy resources already, so each barrel of new, tighter oil is harder to get than the last. We won’t be on “current consumption” levels for thirty, or even twenty years, because as supply goes down and cost of extraction goes up, the price will rise and — hopefully — alternatives will be more competitive and cheaper over time.

So, are you going to start arranging your affairs today? This is the challenge the institute faces.

Cassandra was not believed when foretold the fall of Troy and the institute struggles financially because monied organizations don’t want to amplify what we have to say. Every year we write to foundations, organizations, businesses, and wealthy individuals asking for support, donations, and underwriting — with no result. Well, a negative result is still technically a result. Part of this is admittedly due to my lack of nonprofit fundraising experience (I’m an academic and write successful grants), but I’m now convinced that organizations that have large amounts of money in our current economy no interest in supporting an organization whose foundational premise is: our economy must be fundamentally reformed to be local and self-sustaining. Every endowment, foundation, and corporation large enough to support nonprofits would be defunct in such a future. I realized that I’ve been trying to serve a hederodox ideology to orthodox funding sources. Who cheers for the opposing team to win?

We advocate for DIY solutions for comfortable, self-sustaining households and communities. By definition, if you’re doing it yourself, companies are making less money. We advocate for locally produced food, construction materials, and fibers. Great existing small businesses and artisans that serve finite communities are not wealthy enough to fund nonprofits in their area, let alone those at a distance.

This Isn’t a Complaint, More a Realization

This wasn’t written to complain. I’ve run the Low Technology Institute since 2016. I started the institute in response to my concern — and frankly, depression — after writing about the rise and fall of ancient complex societies in a book: the Romans folding when their economy collapsed as their expansion stopped, the Aztec and Inca failing to unify their respective populations to drive out a few invaders, the Maya unable to absorb a drought, Mesopotamians failing to adapt their agriculture to new conditions, and Egyptian overconfidence in their social superiority contributing to their instability. And with us, it is clear that our inability to accept the coming end of the fossil-fuel era keeps us from proactive adaptation that would make life in the next period more comfortable. The hubris of every society can be an Achilles’ heel, as over-proud people fail to see the need to change their ways.

I’ve joked that we put the “nonprofit” in nonprofit. Financial growth wasn’t our goal. It wasn’t started with an eye to supporting myself or my family — it was started to provide every person, family, and community ideas and tools to adapt to a future without fossil fuels — that and to bring together like-minded people to coalesce behind real-world, hands-on tasks we can do today with an eye to future survival.

My goal in writing this was to exhort you to find a way to help an organization that looks into the deeper future and plans sustainable systems for the natural world and humans’ place as part of it. Look to local community gardens, maker spaces, alternative society groups, and others. Support them with your time and energy. And if you’re in a place where you can lend financial help, do that, too.

As for the institute, we’ll be continuing on as before. We’re grateful for every penny folks have donated, and we use our funds judiciously. We work as hard as we can in the time we have to put out summaries of the research we’re doing here and offer classes to plant the seed of hands-on knowledge in hopes that some of them grow to fruition. The only thing that increased funding would do is free up time for more output. My one regret is that time is finite, and every year that we grow slowly is one year less we have to effect real change in more households and communities.

What Would We Do with Funding?

I sometimes think about an elevator pitch to a billionaire with a penchant for funding unusual organizations. What would we do with a million dollars, say?

We’d raise the quality, quantity, and focus of our research. Specifically, this means tackling on the most important systems to maintain life locally without fossil fuels: water, food, energy, structures, etc. to create simple, DIY solutions for households and communities to support themselves: neighborhood biodigesters, microgrids, intranets, community herds, local time banks, shared community-scale gardens and fields, neighborhood maker spaces, household stockpiling and provisioning — these help us prepare for a long-term change and to weather short-term disruptions.

We’d offer prizes and seed money to initiatives of community self-sufficiency. These would be trial runs of local solutions to fill a need without fossil fuels.

We’d increase the quality and quantity of our outputs: self-fund research that doesn’t fit into existing archetypes and grant applications, step up or production of Bulletin guides, create more and better YouTube videos (especially the R&D series), revive the podcast, and make the blog more regular and substantial.

We’d staff up to get people doing what they’re good at: nonprofit manager, education manager, collaborating scientists, instructors. Almost all of our work has been volunteer hours. We’re proud of what we’ve done with so little and want to show what we could do full time.

Finally, we’d build a timber-frame structure to house our office, workshop, and event space, using our soon-to-be-announced Ten-Mile Building rubric. It’d be a showcase of what can be done in local, low-energy construction.

The Change We Need Isn’t Monetary

This post isn’t meant to be about money, it is meant to be about influence and foresight. Unfortunately today, it is hard to share a message, especially an uncomfortable one, widely without funding. We’re grateful to those who see our work and it resonates with them. But to have a chance at a future for humans (and the basic survival of many of our fellow creatures and ecosystems), we need a sea change in how we think about our world, the economy, and our place.

In the aftermath of World War II, the Swiss government encouraged each household to create a small stockpile — enough to feed and keep each person hydrated for a week. It was not met with instant success. It took a few generations of committed campaigning to make this a common practice among the Swiss. And when the pandemic hit, Switzerland did not experience the hoarding seen in other countries. This is a small example of the type of changes we need to see. But if it took a few generations to get people to keep a few extra kilos of sugar, pasta, and oil around, imagine the challenge we face to convince enough people to overhaul their energy use, food system, and really, whole way of life.

Kurt Vonnegut suggested that we have a secretary of the future in the US presidential cabinet. Long-term thinking is difficult for most human societies, from industrialized instant-gratification junkies to laid-back hunter gatherers. When businesses and people think about “the future” they are at best talking about next quarter, not next year, when we need to be thinking about the next quarter century.

One thing we’re trying to do in addition to developing strategies to house, clothe, and feed ourselves, is to show that we have the option of an abundant future, not just one of deprivation. It would be a different type of abundance, though. Where today we live in a world awash in energy and consumer goods, tomorrow we could have an abundance of community connections, local food, and self-sufficiency. We’ll have to learn prize real individual, household, and community self-sufficiency, not by buying things from far away, but from creating what we need as close to home as possible.

Help us by being an agent of change in your own community.

This last weekend, a friend came for a walk around our village. Rita runs Rye Revival, and we were talking about the trials and tribulations of running small nonprofits. This got me thinking about the institute at a step removed from the day-to-day work and helped me realize that I’ve been trying to serve a hederodox ideology to orthodox funding sources. It is always helpful to chat with friends who think deeply about the state of the world in a quarter century and beyond.

Source link