There are studies in mice/rats that show that swimming increases bone length. But the kind of swimming that rats due is different than the kind of swimming that humans do.

Effects of swimming training on bone mass and the GH/IGF-1 axis in diabetic rats

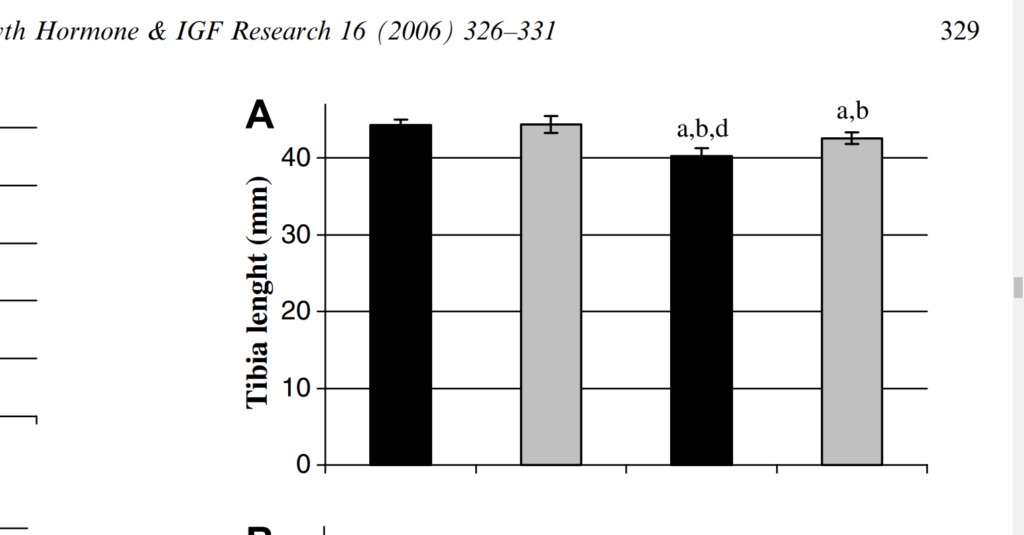

“The aim of this study was to examine the influence of moderate swimming training on the GH/IGF-1 growth axis and tibial mass in diabetic rats. Male Wistar rats were allocated to one of four groups: sedentary control (SC), trained control (TC), sedentary diabetic (SD) and trained diabetic (TD). Diabetes was induced with alloxan (35 mg/kg b.w.). The training program consisted of a 1 h swimming session/day with a load corresponding to 5% of the b.w., five days/week for six weeks. At the end of the training period, the rats were sacrificed and blood was collected for quantification of the serum glucose, insulin, GH, and IGF-1 concentrations. Samples of skeletal muscle were used to quantify the IGF-1 peptide content. The tibias were collected to determine their total area, length and bone mineral content. The results were analyzed by ANOVA with P < 0.05 indicating significance. Diabetes decreased the serum levels of GH and IGF-1, as well as the tibial length, total area and bone mineral content in the SD group (P < 0.05). Physical training increased the serum IGF-1 level in the TC and TD groups when compared to the sedentary groups (SC and SD), and the tibial length, total area and bone mineral content were higher in the TD group than in the SD group (P < 0.05). Exercise did not alter the level of IGF-1 in gastrocnemius muscle in nondiabetic rats, but the muscle IGF-1 content was higher in the TD group than in the SD group. These results indicate that swimming training stimulates bone mass and the GH/IGF-1 axis in diabetic rats.”

Columns: SC – sedentary control, TC – trained control, SD – sedentary diabetic, TD – trained diabetic. So the swimming groups had non-statistically significant increases in bone length between sedentary and trained control and statistically significant between sedentary diabetic and trained diabetic.

Here’s another study that finds an increase in bone length:

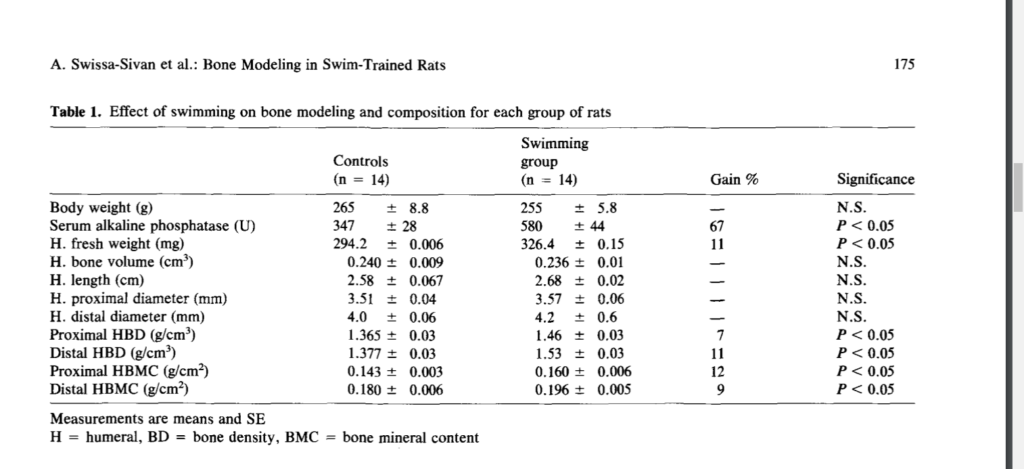

The Effect of Swimming on Bone Modeling and Composition in Young Adult Rats

“The purpose of this study was to investigate the adaptability of long bones of young adult rats to the stress of chronic aquatic exercise. Twenty-eight female Sabra rats (12 weeks old) were randomly assigned to two groups and treatments: exercise (14 rats) and sedentary control (14 rats) matched for age and weight. Exercised animals were trained to swim in a water bath (35°±1°C, 1 hour daily 5 times a week) for 12 weeks loaded with lead weights on their tails (2% of their body weight) (BW). At the end of the training period following blood sampling for alkaline phosphatase, all rats were sacrificed and the humeri and tibiae bones were removed for the following measurements: bone morphometry, bone water compartmentalization, bone density (BD), bone mineral content (BMC), and bone ions content (Ca, Pi, Mg, Zn). The results indicate that exercise did not significantly affect the animals’ body weight, bone volume, or length and diameters. However, bone hydration properties, BD, bone mass, and mineralization revealed significant differences between swim-trained rats and controls (P<0.05). Longitudinal (R1) measurement was higher by 43% for both humerus and tibia, and Transverse (R2) relaxation rates of hydrogen proton were higher by 117 and 76% for humerus and tibia, respectively; fraction of bound water was higher by 36 and 46% for humerus and tibia, respectively. BD, bone weight, and ash were higher by 13%. BMC and bone ions content were higher by 10%, and alkaline phosphatase was higher by 67%. These results indicate that long bones of young adult rats after the age of rapid growth can adapt positively to nonweight-bearing aquatic exercise. This adaptation is evident by an increase in bone mass, density, mineralization, and hydration properties.”

So perhaps upright doggy paddling is a method to induce torsional strain on relevant bones and increase height.

Source link